Make Your Work Into A Gift: How To Become A Genius

What if I told you not only that you are gifted, but that you are a genius. What would you say? Maybe you’d ask back, ‘What does it mean to be a genius? What does it mean to have a gift?’

Lewis Hyde writes in his 1979 book The Gift about the roots of our modern word “genius”: the Latin genius, or what the ancient Greeks call your daemon.

Today we use these words for a select type that we elevate above ourselves: “he’s a genius.” In the ancient world, everyone had a genius.

“The task of setting free one’s gifts was a recognized labor in the ancient world. The Romans called a person’s tutelar spirit his genius. In Greece, it was called a daemon. Ancient authors tell us that Socrates, for example, had a daemon who would speak up when he was about to do something that did not accord with his true nature. It was believed that each man had his idios daemon, his personal spirit which could be cultivated and developed. Apuleius, the Roman author of The Golden Ass, wrote a treatise on the daemon/genius, and one of the things he says is that in Rome it was the custom on one’s birthday to offer a sacrifice to one’s own genius. A man didn’t just get gifts on his birthday, he would also give something to his guiding spirit. Respected in this way the genius made one ‘genial’ – sexually potent, artistically creative and spiritually fertile.

“According to Apuleius, if a man cultivated his genius through such sacrifice it would become a lar, a protective household god, when he died. But if a man ignored his genius, it became a larva or a lemur when he died, a troublesome, restless spook that preys on the living. The genius or daemon comes to us at birth. It carries with it the fullness of our undeveloped powers. These it offers to us as we grow, and we choose whether or not to accept, which means we choose whether or not to labor in its service. For, again, the genius has need of us. As with the elves, the spirit that brings us our gifts finds its eventual freedom only through our sacrifice, and those who do not reciprocate the gifts of their genius will leave it in bondage when they die.

“An abiding sense of gratitude moves a person to labor in the service of his daemon. The opposite is probably called narcissism.”

– Lewis Hyde, The Gift

Philip Pullman’s fantasy book The Golden Compass develops these ancient ideas by describing a world in which everyone’s daemon is manifested as an animal that walks around with you. A bold arctic explorer’s daemon is a snow leopard. A journalist’s is a butterfly. In each case, the animal represents the nature of your daemon and what you have to give the world. Unlike adults, children’s daemons in his book fluctuate between different animals until the child enters puberty and settles into one animal representing her character.

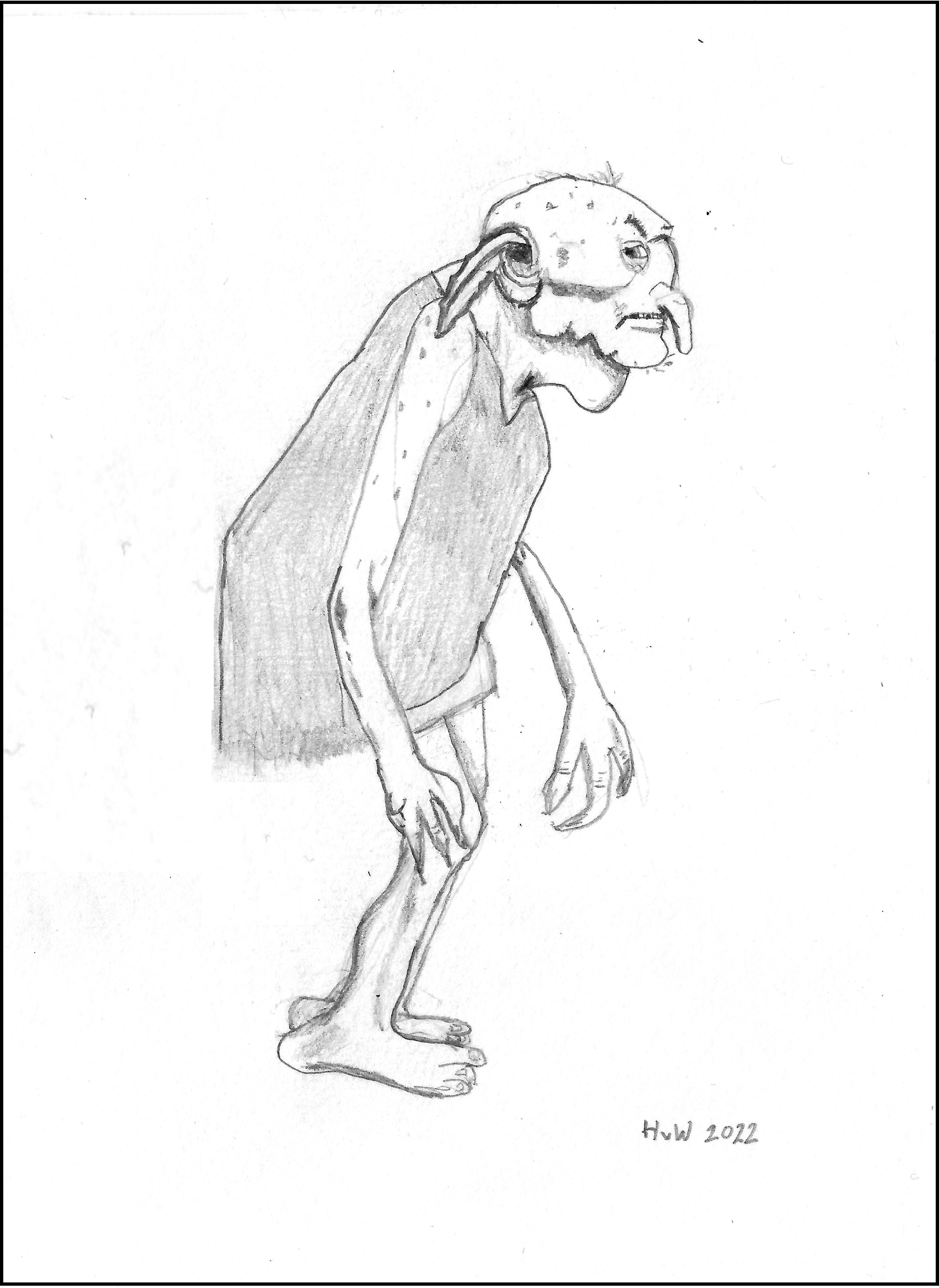

Apeuleius’ lar (a protective household god) or his larva (a troublesome, restless spook) are what our genius becomes depending on whether we accept its gifts and labor in its service: they are Dobbie the house-elf in Harry Potter and his counterpart, the resentful Kreacher. If we refuse the call of our genius, a part of us becomes resentful. This restlessness might manifest in different ways in our life. It might be a persistent low-latency frustration or dissatisfaction. It might be an aggression we direct against the people around us, where we are not quite sure why we are being so negative - like we are casting about to find an external reason for our dissatisfaction, rather than looking inward, where we are most afraid to go. Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art lists the ways this “resistance” pops up: drinking, drug addiction, tumors, neuroses, painkillers, gossip and compulsive cellphone use, to name just a few. Pressfield even attributes his own marital dramas to it.

Harry Potter’s Kreacher is the visualization of this larva resistance. How many of us experience our worklife like Kreacher: feeling in bondage, scattering resentment in unexpected directions, because we have refused the voice inside ourselves - our inner genius? It is in this sense that Kreacher fulfills the modern, negative meaning of the ancient Greek daemon: Kreacher is a demon.

“A genius is the one most like himself.”

– Thelonius Monk

Making your work into a gift doesn’t mean you can’t be compensated. It means that you experience and shape your work as a gift rather than a transaction. Yes, a nurse receives a paycheck. But it’s in bringing her patient an extra pillow that transforms her work into a gift. A computer programmer solving an intricate debugging riddle is getting paid - but in solving a problem that delivers a meaningful package, his work might become a gift. Whether your work is a gift depends on one thing: whether you are listening to your genius.

The best type of work - the most exciting, the most beautiful, the most motivating - is always a gift.

Your genius is calling you, offering up its gifts - so that you can make your life and your work into a gift. Like a tree offering up its flowers, every living being wants to give as part of its growth. These are the true meanings of “being a genius” and “being gifted”.

By elevating “those geniuses” above us – “Yeah he can because he’s a genius. There’s no way I could” – we protect our ego from all the hazards of becoming more than we are.

How can you make your work into a gift? If you find the courage to hear your genius, you’ll discover that you are already are one. Everyone with courage is. In the words of jazz musician Thelonius Monk, “A genius is the one most like himself.”